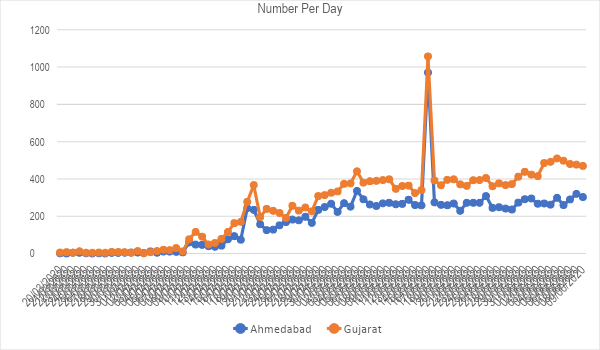

Ahmedabad, with total registered infections of about 14,500 as on June 9, 2020, has remained within the top four cities with Covid-19 infections. Mumbai is leading the list with more than 50,000 infections, followed by Delhi at 28,000 infections and Chennai more than 23,000. These numbers have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as these are reported numbers based on the testing carried out. Testing is done in all cities is of symptomatic persons, who comprise about 20 percent of the total infected. Ahmedabad has driven up the curve of Gujarat state in the number of registered infections per day (Figure 1). As argued by me with another colleague that the high number of infections in Ahmedabad city is because of a segment of population living in ghetto conditions with high crowding (“Why Is Gujarat a COVID-19 Hotspot?”)

Figure 1: Registered cases of Covid – 19, Ahmedabad City (Source: From Daily cases in Ahmedabad)

This issue of public health and morbidity has come up time and again in the history of Indian cities as also in Ahmedabad. Globally as well, scholarship on influenza pandemic of 1918-19 is now getting noticed. In fact, Ahmedabad too was afflicted by influenza pandemic of 1918-19 and also by the plague of 1896 to 1907 and 1916 to 1918. The pandemics have tended to disproportionately afflict the neighbourhoods with high crowding and squalid living conditions, with literary descriptions of miseries and deaths. Viral infections such as influenza, and now Covid-19, spread through air (Corona Virus is Airborne). When people are in close proximity to each other, as in case of crowded living, the spread of viral infections that are airborne or spread of vector-borne infection such as plague is higher.

In the course ‘Ahmedabad as a Gateway to the World’ offered to the first year Bachelor of Arts (Honours) students, majoring in History and Social and Political Science, the development issues faced by the cities are introduced through grounding students in Ahmedabad’s history and socio-political dynamics. To look it in another way; reading of a city tells one the social and political story of a particular era. There is certain uniqueness to Ahmedabad city’s dynamics but there are certain commonalities with other Indian as well as global cities.

The commonalities are: (i) a long history (of about 600 years), with city walls existing of that era; (ii) like many cities of Indian sub-continent a syncretism of Hindu and Islamic traditions manifesting in architecture, textiles, cultural practices, artifacts within the house, and festivals on one hand and simultaneously a practiced distance at individual level; (iii) like most cities in the Indian subcontinent, city structure organized around caste and increasingly religious identities; (iv) the traditional identity-based city structure obtaining an additional layer of segregation by class a construct of the modernization processes; (v) since 1990s, the cities in an attempt to become global cities or what is now referred to as Smart Cities, the mega-infrastructure project driven urban development causing marginalizations and expulsions on one hand and elite gated communities on the other; (vi) the state playing active role in emergence of such fractured cities; and (vii) consequences of all these leading to embedding of conflicts and violence in everyday life of common resident of the city.

The uniqueness of Ahmedabad city is that it is divided by Sabarmati river, that has immense importance in India’s modern history – father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi. Ironically, Gandhian philosophy is about integration while Sabarmati river today divides Ahmedabad into the east and the west. During the two-month lockdown period, the police blocked movement across the five bridges that bridged the two sides, physically, economically and socially! The west, that of the elite, not wanting to have any physical contact with the east for the fear of virus spread.

The second uniqueness of the city was that during 1917 to 1928 period, Sardar Vallabhai Patel was a member of the Municipal Commission of Ahmedabad, which he led from 1924 to 1928 as its President. After the British government, adopted the principle of local self-government in India under the Viceroyship of Lord Ripon, the first elections in Ahmedabad Municipality were held in March 1883. The first Chairman of the Ahmedabad Municipal Commission, Ranchodlal Chhotalal (the pioneer of cotton textile industry in Ahmedabad) proclaimed: “The most important duty of the Municipality is to look after the public health.” (Gillion 1969: 136). As a President of Ahmedabad Municipality, Sardar Patel, paid special attention to improving the poorer localities of the city, extended water supply and drainage lines and planned gardens, parks, and playing fields for schools, and various other urban planning efforts including opening up the residential areas through planned intervention on the western bank of river Sabarmati.