Minal Pathak, Associate Professor at the Amrut Mody School of Management and the Global Centre for Environment and Energy, and drafting author on the recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, was in the UK when the heatwaves disrupted everyday life across the region. In a Q&A with The Stepwell, she outlines how India's initiatives to manage heat could help other global cities tackle extreme heat events.

Professor Minal Pathak, you experienced the European heatwaves firsthand. Were the on-ground conditions an indicator of how immense the risk of continuing heatwaves is?

At 40°C, London, where I was, was unable to cope, right from the railway infrastructure, which virtually shut down, to the discomfort of staying indoors. Ironically, the iconic buildings that impress us as beautiful pieces of architecture now pose a threat to human wellbeing, even life. What the region has been witnessing since June this year has made us realise that these historic buildings are not built to handle this unprecedented heat. The conditions were quite distressing, and Europe needs to prepare itself for similar heatwaves in the future.

What are some consistent patterns you observe in the regions experiencing heatwaves?

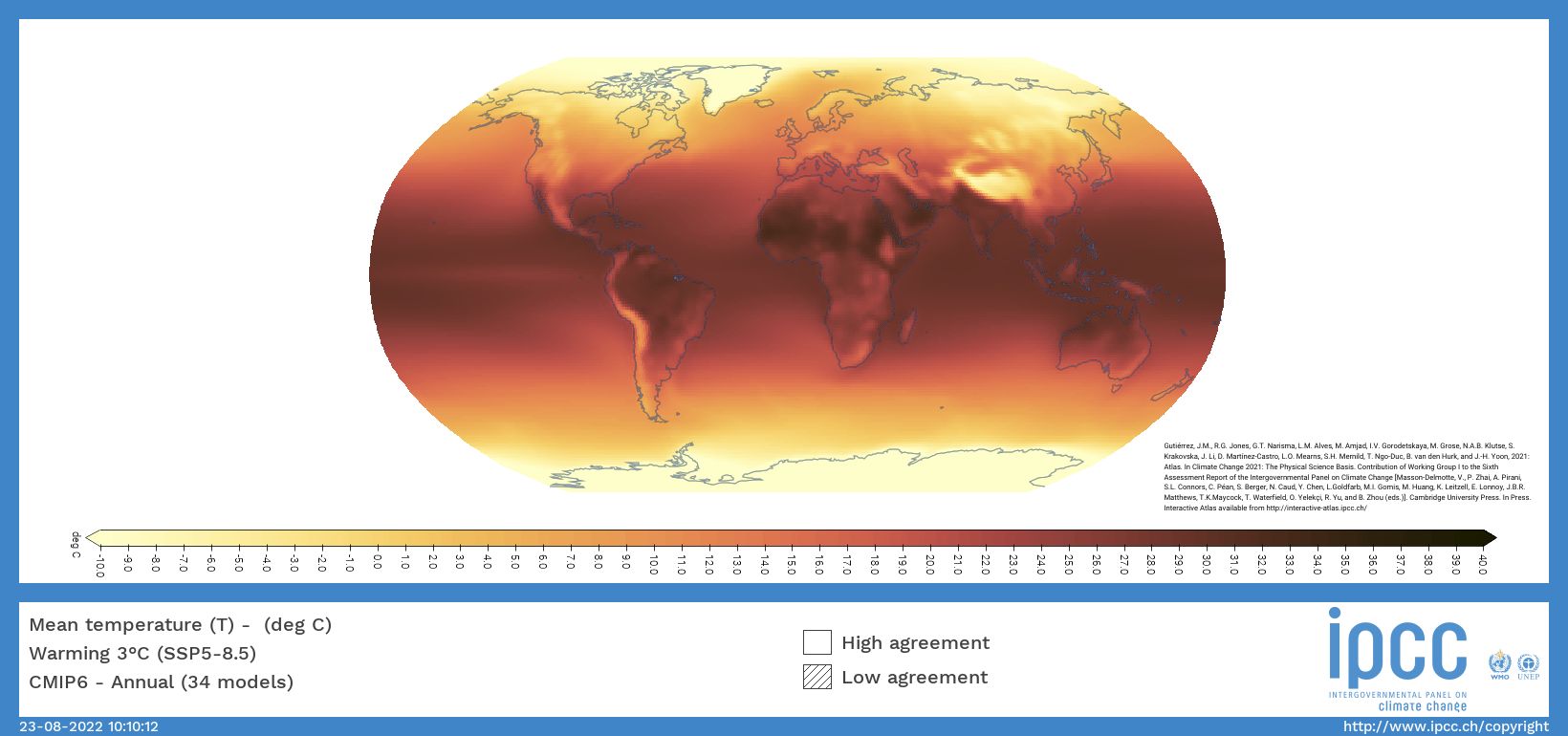

The devastating heat waves sweeping across Europe and South Asia have finally drawn attention to a pressing issue that scientists have been warning about. Heatwaves are a stark warning of the climate emergency we are in. But, a little too late, perhaps. This is not just a climate change issue - as we see adverse impacts on people's health and wellbeing, the economy, and industry. Much has been written in South Asia about the damage to crops, school shutdowns, and the impact on millions of informal workers who do not have the luxury of staying indoors and cooling off. Access to cooling is a luxury to many as the proportion of people living in informal households ranges between 25 to 50 per cent. This accessibility and affordability will now be challenging for many regions as temperature records are being broken. Effective and dynamic urban heat action plans will need to be supported by actions such as climate-responsive urban planning and building design, green and permeable surfaces, and cool roofs in urban areas can help reduce the impacts of heatwaves on people.

As part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Crisis (IPCC) and a climate scientist who speaks untiringly about immediate as well as holistic action, what policy measures do you think need to be undertaken immediately?

Our recent IPCC reports clearly indicate that along with policy shifts, community response to the situation, by which we mean individual response as well as that of the private sector, is critical if we need to control this pressing climate challenge. And now is the time, if ever we can do it. Not in 2025, as most people believe, not tomorrow, but today. It is the collective responsibility of all stakeholders (industries, businesses, institutions, NGOs, citizen groups, and people) to help achieve the transition that leads us to a low-carbon climate-resilient future. For cities, the IPCC report identifies three broad strategies to be effective when implemented concurrently to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: Reducing or changing energy and material use towards more sustainable production and consumption, using electric vehicles when powered by low-carbon energy sources such as renewables, and enhancing carbon uptake and storage in the urban environment, for example, through bio-based building materials, permeable surfaces, green roofs, trees, green spaces, rivers, ponds, and lakes. Solutions such as passive building design, shaded and walkable areas, transport infrastructure adaptable to future heat events, and nature-based solutions can be effectively implemented across cities.

In response to heat events, in which areas has India shown success? And could these set an example for other regions across the world?

Despite the initiatives undertaken, India has an uphill task ahead as our development status, economic growth, and natural endowments compound future climate change challenges. As a developing country of over one billion people, the demand for energy and materials will continue to increase to meet the growing demand for land, materials, and energy. Much of this is currently dependent on fossil fuels. Presently, several countries are battling the same concerns about energy security.

While India builds on initiatives that have shown success, the West could look at these for possible solutions. India has shown remarkable success in upscaling renewable energy, LPG, and an ambitious proposal for a complete transition to an all-electric vehicle fleet by 2030. The country has seen an increase in demand for electric two- and three-wheelers. We have seen the benefits of converting public transport to electric transport based on reductions in greenhouse gases and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions. Policy decisions toward efficient air conditioning, a shift to LED lighting, and industrial efficiency, to name a few, were reported to have saved India 25 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2019-2020. That led to avoided emissions of over 150 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2). Our solar programme is a crucial element that can help mitigate climate change. Still, it needs to be evaluated vis-a-vis energy alternatives like green hydrogen, nuclear or carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS).

How a 'hot' country like India responded to the heat waves would be worth mentioning here as an interesting study for Europe. A year after the 2015 heat waves, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) published guidelines on preventing and managing heatwaves. While acknowledging that heat waves were not listed as a "disaster" under the Disaster Management Act, 2005, it also accepted the urgency of heatwaves management. It urged cities and states to prepare Heat Action Plans (HAPs) that focus on early warning systems, training healthcare professionals, raising public awareness, and encouraging collaboration with NGOs and civil society. The Ahmedabad HAP, launched in 2013, was highlighted as a model to follow. Since then, many Indian cities, including Delhi, Hyderabad, Bhubaneswar, and Nagpur, have developed HAPs, while some states like Maharashtra and Odisha have also formulated state-level HAPs.

While HAPs try to manage the disaster by focusing on early warnings, it will need a more transformative approach to mainstream climate change in urban planning and policy for this plan to work. And in Europe, this is the area that needs to be on equal priority, alongside early warnings and community help. European governments and policymakers in developing and developed countries must consider long-term urban planning measures, forms, building guidelines, and infrastructure to prevent and minimise heat-related impacts on cities.

A more recent scientific understanding is around compounding risks -- where cities will face simultaneous climate challenges. With the expected climate risks, urban areas must take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and implement measures to enhance adaptation to extreme weather events from climate change. Enhancing green and blue spaces in cities, encouraging public transport and reducing private transport use, investing in electric vehicle charging infrastructure, mandating climate resilience in building codes, improving the energy efficiency of public infrastructure, and better waste management could deliver a large number of benefits to Indian cities.