When Nandish Patel, pursuing a BA (Hons) in Economics at the Amrut Mody School of Management, was working on a term report for his course on History of Economic Thought, he decided to delve into some of the lost economic ideas from ancient Indian texts and epics. He started by discussing the Puruṣārtha concept ('Objectives of people' - Dharma, Artha, Kāma, and Mokṣa) in the light of individual motives, arguing how welfare was always understood to be multi-dimensional in ancient India.

Aneri Dalwadi, a final year BTech student studying Computer Science and Engineering along with Ahmedabad Alumnus Dhruvil Dave (then in his final year of BTech) invented a new syntax and created a novel tool to transliterate and input/output Sanskrit. Named UAST (Unicode Aware Sanskrit Transliteration), this tool eliminates the barrier to reading and writing Sanskrit using computers.

School of Arts and Sciences' Poojan Patel, pursuing a BA (Hons) in Philosophy, History and Languages, connected his knowledge of Sanskrit with his Performing and Visual Arts course, 'Archives of Artistic Practices in Modern South Asia'. As part of his submission, he worked on a project comparing the miniature paintings on the Gītagovinda in the LD Museum with the original Sanskrit poetry.

Why should one study Sanskrit today? It doesn't check the box as a lucrative field. Whoever heard of Sanskrit graduates being hired? If nothing, it is perceived as a language steeped in orthodoxy. Through Ahmedabad University's Sanskrit courses offered under the Philosophy, History and Languages major at the School of Arts and Sciences, students are discovering the deep connections that Sanskrit has with whatever we do. Shishir Saxena, Assistant Professor in the Humanities and Languages division of the School of Arts and Sciences, says, "The Sanskrit study at Ahmedabad University is young – our oldest students are now in their third year of study – but it is ambitious and adventurous! The myriad scholastic traditions of Sanskrit – philosophy, poetry, mathematics, medicine, music, aesthetics, and many more – have been and are studied by scholars across the world. The urgent need of the hour is the nurturing of serious Sanskrit scholarship. In this context, our students' thought-provoking work using their knowledge of Sanskrit in multiple disciplines becomes quite significant."

A BBA (Hons) student majoring in Accounting and Finance, Hitankshi Shah, says, "Being a business management student, for me, Sanskrit has been that anchor which reminds me of the origin of great pieces in the area of business such as Arthshashtra. These have concepts that are used as reference points even today. Learning Sanskrit has allowed me to read original texts written thousands of years ago. It contrasts how people believe that the language has no scope or narrow implications where it is just the contrary."

Her colleague Nandish explains how he used Sanskrit to decipher Economics principles in ancient India. "Before the rejections of the Rational Agent theory in Economics, ancient India always saw welfare as multi-dimensional. I looked into Śukrāchārya's views on the Theory of Price and how he adopted a dualistic approach to value determination- considering both the cost of production and the perceived utility of a commodity. Finally, I picked up the domain of Public Finance and Taxation, discussing some ideas of Bhīṣma from the Śānti Parva of Mahābhārata and of Cāṇakya from the Arthaśāstra, that can be viewed as ancient precedents of modern economic theories." In the end-term report, Nandish provided arguments for the structural integrity of the well of economics, defending it from two principal arguments. The first questioned if the Indian tradition allowed any scope for economics or optimum utilisation of resources, and that, with its extensive focus on liberation or salvation, how could there be any lessons for worldly pursuits. "It is also widely believed that what little may be found on economics in ancient India is just in the form of doctrines for a king to maximise his interests. The argument suggested that the idea of applying economics for the welfare of people developed with the inception of democracies. I drew my defences from the Indian schools of thought [Darśana(s)], with a special mention of a school that preaches materialism (Cārvāka), the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and other relevant sources," he says.

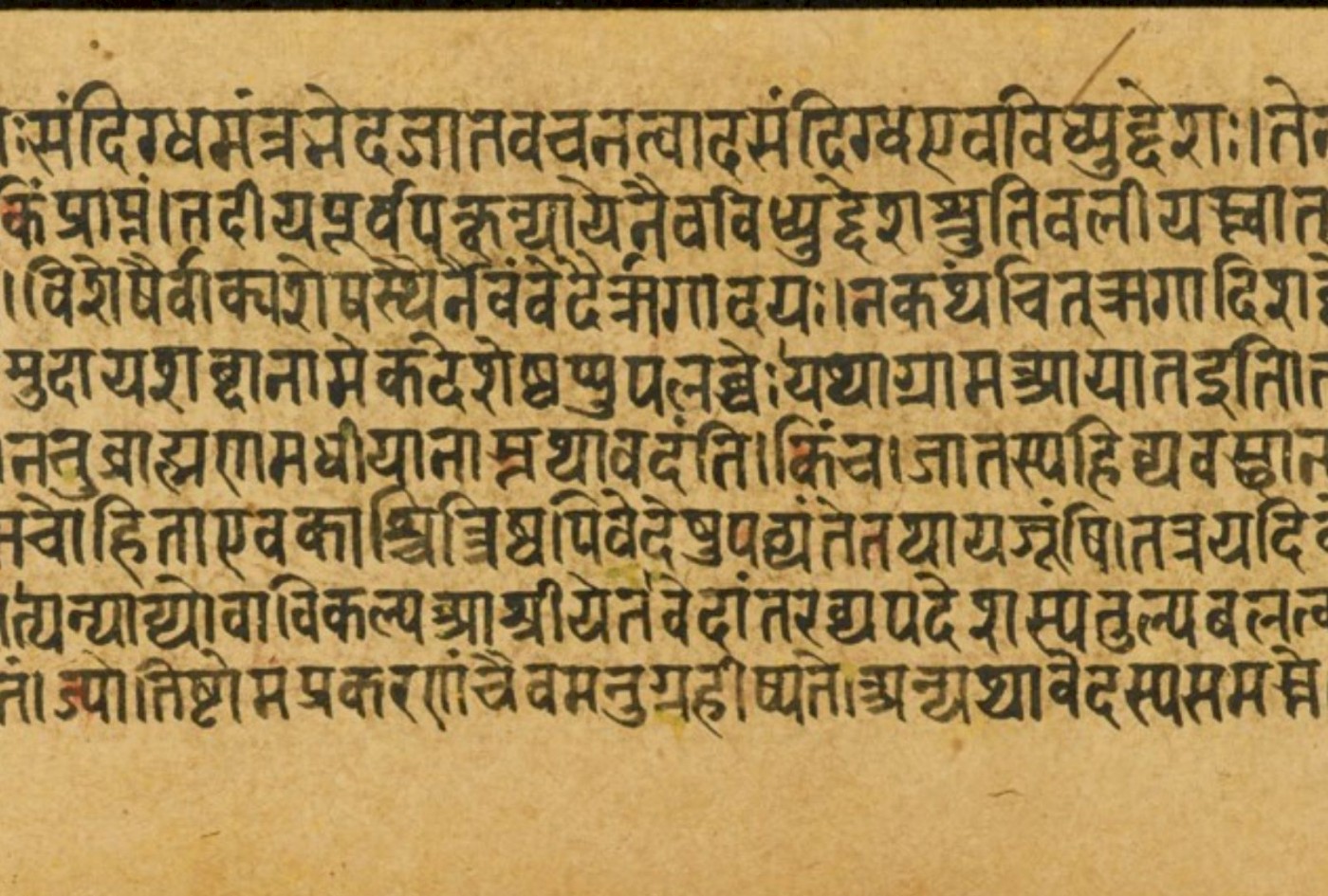

The stability of Sanskrit is an outstanding feature of the language. Unlike other languages, Sanskrit has changed little over the course of over three millennia allowing intellectual conversations in the language to stretch across temporal boundaries. The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST), a scholastic method of romanising the Devanāgarī script, is one of the first things students are taught in the Sanskrit courses. Professor Saxena says, "However when it comes to typesetting Sanskrit with IAST on a laptop, we have to use non-ASCII Unicode characters, which creates a problem of having to use non-standard key bindings and/or packages to input those characters."

Until now, this was a barrier as there were only a few tools that would help computational linguists and computer scientists with transliteration. That's how Aneri and Dhruvil teamed up to invent the UAST. Aneri, the primary author of the study subsequently published online, was the primary inventor of the syntax and creator of the software. Dhruvil, now pursuing his MS in Business Analysis at the University of Texas Dallas, worked closely with Aneri on UAST. He says, "This is an unprecedented tool and mathematically the fastest too. It is based on Unicode, the backbone of information encoding that powers 95 per cent of the internet. We hope that UAST reaches the maximum number of people as reading and writing Sanskrit using computers is hassle-free with UAST."

Poojan Patel, when looking at the 18th century paintings of Manaku at the neighbouring LD Museum, found that they had been directly inspired by the 12th-century Sanskrit poem of Gīta-Govinda by Jayadeva. He says, "When the beauty of the paintings beckoned me, I could read only so much from the apparent. The apparent beauty compelled me to enter deeper and look into what was behind the artist's inspiration. Surprisingly, each painting had, on its reverse, the corresponding verses inscribed." The 12th-century poem was in Sanskrit, and Poojan could read those verses in their original language. Based on that, he did a project titled Bhakti: Sung and Painted, in which he attempted a literary, visual, and philosophical exploration of these two works of art around the central theme of love for a Performing and Visual Arts course. Poojan says, "Sanskrit is the key to open up many treasures of art in the forms of poetry, music, architecture or painting or the great intellectual and philosophical treasures of the Vedas, Upaniṣads, darśanas, or the śāstras and the sūtras of many disciplines. So I would consider Sanskrit, rather than ancient, a timeless language." Currently, Poojan is working on his undergraduate thesis on the Īśā Upaniṣad, where he is studying the verses, both philologically and philosophically based on the commentaries of the same text by two prolific scholars, Ādi Śaṅkara and Sri Aurobindo.

Professor Saxena says, “Ahmedabad University allows anyone across the University to take a Sanskrit course, and that’s remarkably rare in the Indian context if not altogether unparalleled. Additionally, we are giving the language a serious research focus by deliberately taking a scholastic approach. For our senior classes, we explore the depths of the language by reading original texts. Sanskrit is, after all, an intellectual tradition.”