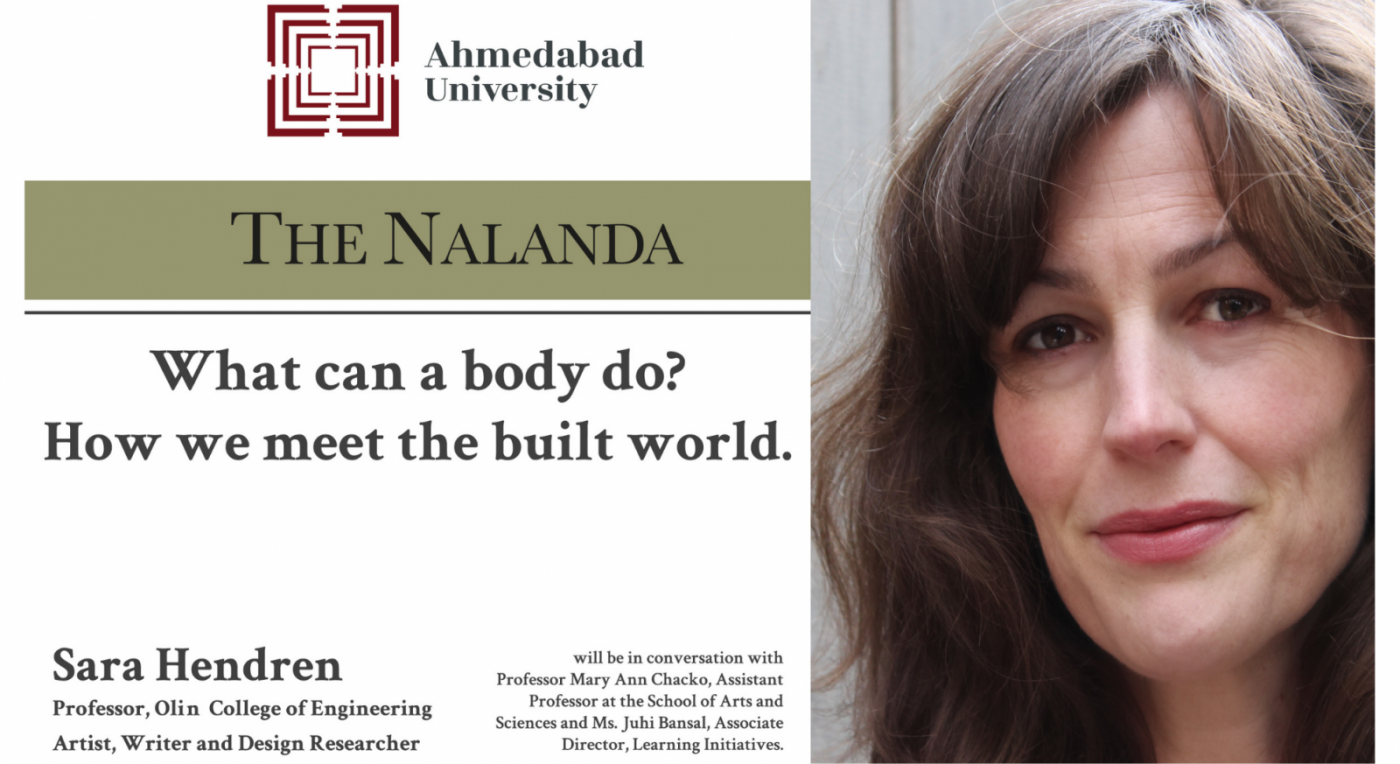

The Nalanda : What can a body do? How we meet the built world.

On 3 rd February, 2021, Professor Juhi Bansal, Associate Director at Learning Initiatives, and Professor Mary Ann Chacko, Assistant Professor at the School of Arts and Sciences were in conversation with Professor Sara Hendren, artist, design researcher, writer, and professor at Olin College of Engineering. The talk, titled "What can a body do: How we meet the built world" , was an insightful conversation on how we view the idea of disability in conjunction to the built world around us.

Professor Hendren began with a presentation outlining the major themes of her book, alongside some crucial examples that set the stage for the subsequent conversation. Commencing with design of the book-jacket, Professor Hendren emphasised that the lettering – which bleeds out of the jacket from the edges – was deliberately designed to ponder on the idea of misfitting. The unanswered question of “Is the type to big or the book too small?” becomes analogous to “Is it the world that might need to change and shift its properties or is it our bodies that need to adapt?” – a query that the book itself is concerned with.

As the presentation proceeded, it illuminated how ideas of tech-oriented assistance in disability – such as high-tech prosthetics – can come with the idea of removing assistance altogether from life. As she argues, however, assistance is something that keeps us connected, and to that extent is not just necessary but can also be desirable.

Through the course of the talk, Professor Hendren remarked on the idea of Misfitting, saying that while there is the idea of a square peg in a round hole – the idea that either the environment is not made for you or you are not designed to fit it – it must be remembered that there is no way to tell on whom the onus of ‘fitting in’ lies. This raises questions of where we should intervene, in an adaptive world, especially using tech.

As she emphasized, our view of tech interventions ought not to be limited merely to making a transhuman body modifications – such as high-the prosthetics or enhanced cochlear implants – but also to redesign the world around us in small and simple ways to make it more hospitable to everyone. As an example, she note how designing walls with monochrome colours (light blue and green) rather than colourful and decorative ones in an all-deaf college campus, assists in distinguishing the nuances of sign-language easily. For many, this is vastly more preferable than having cochlear implants, she said.

Towards the end of the talk, in response to Professor Chacko and student questions, Professor Hendren expounded on the idea of an anticipatory way of thinking of disabilities. She recalled Steve Saling, a designer who began to design a tech-driven residence for people with ALS and MS, when he himself was diagnosed with ALS. Noting how powerful it can be to make anticipatory designs in the environment to make it equally habitable, even as one changes one’s relations with one’s own body is a very powerful and poignant idea; a good life, a life worth living, can be led with the right design impetus, despite ones changing relations with one’s body. To this extent, tech, especially AI, is most definitely crucial.

At the conclusion, prompted by Professor Bansal, Professor Hendren spoke on her idea of “body- plus” – a term she coined to refer to all the assistive tech we use regularly as part of the extension of our bodies; not just devices such as smartphones, but also pencils, spoons, eye-glasses or even clothes. Encapsulating the idea of Body-Plus succinctly, she said we no longer have an image of a utopian human without extensions that assist them – they are deeply engrained in us now (they assist us) in ways that we do not necessarily bemoan and in fact celebrate. Just as we require clothes or spoons, perhaps we could design the world around us for people with disabilities to recognize their extensions. After all, the fact of having disabilities proceeds from the fact of having a body,